The Fundamentals of Animal Testing in Clinical Research

Because humans and animals are biologically similar, animal testing in clinical research helps researchers learn how to prevent, treat, and cure human diseases and ensure product safety.

Source: Adobe Stock

- While several different approaches are used during clinical research, traditional biomedical research involving animal testing to develop new treatments and drugs may be a strategy of the past after the FDA Modernization Act 2.0 was signed in December 2022. This act allows organizations to use scientifically rigorous, proven, non-animal testing methods, such as cell-based assays and computer models, when suitable.

Animal Testing

Dating back to 500 BC in ancient Greece, animal experimentation has been used throughout history in the field of biomedical research. Animal testing allows researchers to examine health problems affecting humans and animals and assure the safety of new drugs and medical treatments.

Today, standard animal models typically include mice and rats because of their anatomical, genetic, and physiological similarity to humans and their ease of maintenance and size, short life cycle, and abundant genetic resources. According to Missouri Medicine research, rats, mice, and humans have approximately 30,000 genes each — roughly 95% of which are shared by all three species.

The European and North American house mouse (Mus musculus) is biomedical research's most commonly used experimental model organism. However, for behavioral and physiological studies, rats are most commonly used because they are more social and mimic human behavior better than mice. For more than 150 years, the laboratory rat (Rattus norvegicus) has remained the choice model for these complex fields of study.

Using new gene-editing tools, such as CRISPR-Cas9, scientists can make precise changes to the genomes of larger mammals, such as primates, pigs, sheep, dogs, cats, rabbits, hamsters, and guinea pigs, to learn more about diseases, disorders, and prevention and treatment methods that affect both humans and animals.

Non-human primates (NHPs), a group of hominins, apes, and monkeys that are biologically and evolutionally similar to humans, are used in several research fields because they are susceptible to many of the same health problems and because they have short life spans, making it easy for researchers to study entire life cycles or several generations.

The NHP species most commonly used in biomedical research are macaques (Macaca mulatta) due to their affordable breeding and housing requirements and suitability as a model for high-priority diseases like HIV, obesity, and cognitive aging.

Animal Welfare

Although federal organizations have developed clinical laws and regulations to make animal testing more humane, the practice of using animals for biomedical research has been under intense scrutiny by animal rights and welfare groups for many years for their lack of oversight into the treatment of excluded animals.

What Is the Animal Welfare Act?

Passed in 1966 and enforced by the USDA and APHIS, the Animal Welfare Act (AWA) addresses how warm-blooded animals are cared for and treated in laboratory settings regarding their housing, feeding, cleanliness, ventilation, and medical needs. The act also requires using analgesic drugs for potentially painful procedures and interventions.

However, in a provision of the 2002 Farm Bill, laboratory rats, mice, and birds were explicitly excluded from the Animal Welfare Act, ending a longstanding debate among animal rights advocates and researchers over whether the USDA should be responsible for regulating certain species of rodents and birds bred for research purposes. The act also excludes horses not used for research and farm animals.

Several government organizations, including the United States Department of Health and Human Services, the Public Health Service, and the Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare, control the use of mice, birds, and rats in laboratory research. A separate piece of legislation, the Health Research Extension Act, sets the standard of care and housing for mice, rats, and birds excluded under the AWA if federally funded.

What Is the Health Research Extension Act?

The Health Research Extension Act of 1985 provides a legislative mandate for creating and enforcing guidelines for the care and treatment of animals — such as mice, rats, and birds — used in biomedical and behavioral research funded by the Public Health Service (PHS).

AWA-covered facilities that use animals for research, testing, or educational purposes are required to form an Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) — comprised of scientists, veterinarians, and at least one member of the general public who is not institution-affiliated — to oversee their animal programs. With roughly 1,400 IACUCs associated with research, testing, and educational laboratories across the US, these committees are responsible for inspecting laboratories and teaching facilities.

Before animals can be used, IACUCs are required to review and approve all research and education protocols. To minimize suffering, they also look for evidence that the investigator has genuinely tried to identify animal alternatives if the research might cause painful or distressing sensations.

If it is decided that animal subjects must be used, IACUCs ensure a plan is in place for alleviating pain and distress. To assist institutions, the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, an internationally accepted primary resource for animal care and use, is required for the proper care, use, and humane treatment of research animals.

How Many Animals Are Used in Research?

Although alternative non-animal models exist, the Humane Society of the United States estimates that more than 50 million animals are used in research, education, and testing yearly in the US. Globally, the RSPCA suggests that more than 100 million animals are used in research and testing each year.

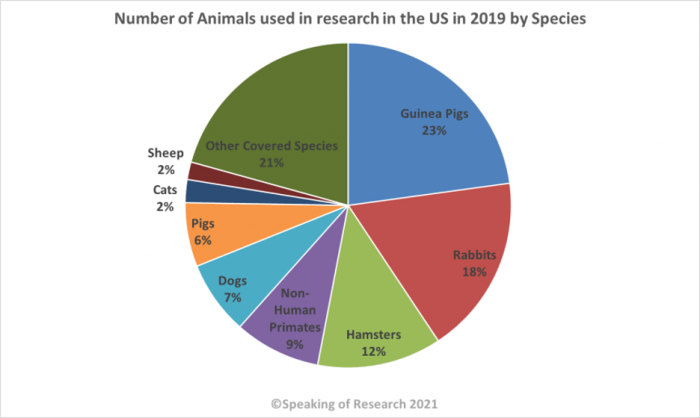

In 2019, data from the US government suggests that 797,546 laboratory animals were used in research — an increase of 2.2% from the previous year — and that 137,225 animals were kept in research facilities but were not utilized in any studies.

United States animal research statistics from 2019 indicate that 53% of research was conducted on guinea pigs, hamsters, and rabbits, while 9% was conducted on dogs and cats and 9% on NHPs.

Globally, roughly 100,000–200,000 NHPs are used yearly for research purposes. According to Columbia University, the use of NHPs is on the rise as they have been proven particularly valuable in monoclonal antibody research, in which NHPs are the only animal approved for preclinical safety studies.

Because the AMA excludes mice, rats, and birds, the US does not track how many of these animals are used for research each year. However, some suggest these numbers may be comparable to other developed countries that do.

For example, in Great Britain, 2.88 million procedures were carried out in living animals in 2020, with a majority (92%) of procedures performed on mice, fish, or rats. According to Stanford University, approximately 95% of the total animals needed for medical and scientific purposes in the US are rodents.

When possible, researchers are committed to conducting studies using alternative methods, including cell-based testing, 3D tissue cultures, computational and mathematical models, noninvasive diagnostic imaging, and human testing instead of animal models. However, some health conditions, unfortunately, can only be studied in a living organism to ensure human safety and efficacy.